Why Abbeys? The Mission of Icolmkill House: Part I – History

Why Abbeys? The Mission of Icolmkill House: Part I – History

The History of Gaelic Christian Abbeys Spreading the Faith and Creating Western Civilization

The Christian faith was born with Jesus, the Man who split time and history. By 380AD Christianity had become the state religion of the vast Roman Empire which within the next 100 years disintegrated into pagan barbarism with the Fall of Rome. In the West, Christianity faced extermination. Yet, by Christmas Day 800AD, Charlemagne had united a Christian Europe and was crowned Holy Roman Emperor. How did Christianity survive? Gaelic Christian Abbeys were islands of life, lamps of light scattered across a dark continental sea of brutal barbarity. The Abbeys formed the crucial link that bridged the fifth century to the ninth, and sustained a faith that would flourish as the foundation of Western Civilization.

Christianity had ascetics early on, notably the Desert Fathers of Egypt in the 3rd century. Monks, the Greek name meaning solitary, sought to withdraw from society to isolated locales to live out lives of austerity, labor, study and worship. Monks clustered together became known as monasteries, rough modes of communal monastic life.

Christianity entered the British Isles in the 1st century during the lives of the Apostles, carried by sea traders and merchants and legionaries traveling along the incomparable network of Roman roads. Beginning in 43AD Rome had quickly conquered the tribes of Britain and established Provincial rule, but the greatest military power in the world, over four terrible long centuries of sometimes genocidal aggression, never conquered the freedom loving tribes of Caledonia whose culture remained ‘remote from the Roman experience.’

Gaels in Ireland, Wales and Scotland were early adopters of Christianity perhaps owing to the great compatibly with many beliefs and traditions of ancient Clan social life and Druidic spiritual life. Monks in the tradition of the Desert Fathers began to seek isolation for lives of devotion near their watery deserts among the many islands and remote peninsulas and establish monasteries as models of spiritual living: following Christ in prayer, humility, labor, ministry and the call to missions.

In 397AD a Gael named Ninian established the earliest known church and monastery in what would emerge as Scotland at the Candida Casa, which became an important locus for pilgrimage and launch pad for missions. In the 5th century, Patrick, son of a Candida Casa church family, was captured by pirates and held as a slave in Ireland for 7 years. Patrick escaped and made his way home, but soon left his family to return on a mission to Ireland, eventually establishing a network of monasteries and Abbeys and earning the name of St. Patrick, Apostle of Ireland. Of the growing monastic fervor among the people, he wrote that he was taken by the number of sons and daughters who sought to live as “monks and virgins for Christ.”

By the sixth century Gaelic Christian monasticism had taken hold culturally and more than 100 monasteries of great significance were established throughout the country and islands, eventually developing into abbeys endowed by the leading families and led by lay Abbott and Abbess members of the clans.

In 563AD Columba, prince of a prominent family, founded Iona Abbey and ignited a spark that grew into an all consuming flame of Christian civilization. The Gaels were a tribe of the Celts whose culture spread widely across the Western world. The Abbey became a center of spiritual and cultural ascendance, attracting those sons and daughters yearning for worship, knowledge and training in the Christian life from vast distances across every point of the compass.

A Saxon prince from Bernicia was exiled to Iona in 616AD where he converted to Christianity and gained a spiritual and practical education. He returned home to conquer his neighboring nation Deira and unite with them into the kingdom of Northumbria, for two hundred years the largest and most powerful of the Anglo Saxon heptarchy. As King, Oswald sought to bring his subjects under the beneficial influence and providence of God and in 634AD called on Iona to send an Abbott to found a new Abbey in his Kingdom. Iona sent Aiden, who with Oswald established Lindisfarne Abbey on the tidal Holy Island, soon to become the greatest Christian Center in Britain.

It must be remembered that the whole of the British Isles beyond Gaeldom was lost to Christianity with the withdrawal of the Romans around 400 and the investment of the pagan Anglo Saxons. There was no Christian influence save for the Gaelic Abbeys and their missionaries from the West: no Roman Catholic communication until Augustine sent Gregory on his mission to Kent in 597; no British Church for over two hundred years during what Gildas called ‘the groans of the Britons.’

The establishment of the Abbey of Lindisfarne inaugurated the great spread of the faith throughout the land with the construction of dozens of daughter houses directed by Abbots and Abbesses of the leading local families. The expanding network of Abbeys penetrated the culture deeply leading eventually to the conversion of the seven kingdoms of the heptarchy of pagan Angle Land and their unification into what would become Christian England.

Among the most significant developments of the Gaelic Abbeys of England, monks educated and trained at Lindisfarne created unrivaled works of art and scholarship while founding and serving in numerous descendant monasteries and Abbeys establishing a direct line in the advance of Western Civilization. In but one example, Ceolfrith, a monk from Lindisfarne trained under Aiden, became Abbott at Monkwearmouth Jarrow where he discipled Bede, who authored the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, a history of the church in England. It was completed in 731AD and today the Venerable Bede is known as the Father of English History. One of Bede’s students, Ecgbert became Abbot of York in Northumbria where he tutored Alcuin. Alcuin rose to become head of the school and library at York, in its day known as the greatest library in Christendom. Returning from a book collecting trip to Rome, Alcuin was introduced to Charlemagne, the Frankish Emperor.

As Christianity disappeared from the British Isles with the collapse of Rome, so it was the case on the Continent where barbarians from the East swept across the frontiers beginning in 406 to destroy Roman power, administration and culture. Four centuries later, Charlemagne succeeded in conquering his rivals and, envisioning a European empire of common culture, required first the creation of culture from the consolidated tribes of illiterate pagan barbarians. The Emperor called Alcuin of York to his Palace School at Aachen to civilize his family, the court and his kingdom. What followed was another remarkable point of civilizational advance, as Alcuin’s programs for language, literacy and learning sparked what historians call the Carolingian Renaissance. In fact, from Alcuin’s Palace School a direct line can be drawn to the foundation of the University of Paris centuries later. Charlemagne achieved much of his dream. He was crowned Holy Roman Emperor on Christmas Day 800AD, Alcuin offering the gift of his new personal translation the Bible into Latin.

It was the Gaels that Christianized England and prepared Northumbria as a second homeland for launching missions to the Continent. Of course Alcuin was not alone in carrying the blessings of Christianity to the wider world. Alcuin himself wrote,

“This race of ours, mother of famous men,

did not keep her children for herself,

but sent many of them far across the seas,

bearing the seeds of life to other peoples.”

From England, during the 8th century great missionaries like Wilibrord and Boniface crossed the channel and traveled widely converting everywhere they went; Boniface known as the Apostle to the Germans and Wilibrord Apostle to the Frisians. These men are responsible for converting Germany and the low countries to Christianity and expanding civilization and culture.

Thousands more monks left the Abbeys of Ireland and Scotland as perigrinatio pro cristo, or pilgrims for Christ. Schottenkloster (House of the Scots) became a common German term for these monasteries spread across Continental Europe in the Middle Ages by Gaelic missionaries, known as the ‘teachers of kings and disciplers of nations’. The most accomplished is Columbanus, who traveled with 12 companions from a Gaelic Abbey to France in 590AD. Columbanus and his brothers in faith founded landmark Abbeys in France, Germany, Switzerland and Italy. For brevity, we will feature the opinions of the experts in describing what Columbanus created. According to Columban biographer Dubois, “the monastery at Luxueil was to become the most brilliant center of learning and virtue in the Middle Ages.” Continuing, he wrote that Bobbio Abbey “became from the first century of its foundation, an intellectual center of incomparable radiance; the learning and holiness of the monks illuminated Northern Italy; the richness of its library astonished the world of the humanists, and for nearly a thousand years this privileged abbey experienced a marvelous expansion.” Zimmer writes, “St. Gall was the most celebrated monastery in Germany at that time and for more than three hundred years it was looked upon as the chief nursery of learning of the whole kingdom. It owes its reputation greatly to its connections with the Gaels and the work of learned Gaelic monks in its university.”

Clark described St. Gall as follows. “Books were written, copied, and illuminated in the scriptorium. Musical works were composed, and the theory of music was taught. The monks observed the sun and stars to calculate the dates of church festivals. All the sciences known in that day were diligently studied, nor were the more practical arts and handicrafts neglected: painting, architecture, sculpture in wood, stone, metal and ivory, weaving, spinning, and agriculture were all the object of assiduous attention. Among the monks of St. Gall there were historians, theologians, artists, poets, and musicians.”

In 1950 Robert Schuman, a founder of the European Union, said that, “St. Columban is the patron saint of all those who now seek to build a united Europe.” And John Costello, stated, “History records that it was by men like him that civilization was saved in the 6th century.”

Gaelic monks and their Abbeys not only saved civilization but formed the stepping stones upon which Western Christian Civilization continued to advance across the West to previously unimagined heights for the betterment of the entire world. The watersheds of Western Christian Civilization are directly linked to Gaelic Christian Family Abbeys. We recalled how Alcuin of York ignited the Carolingian Renaissance in 789AD, followed by the unification of Christian Europe under Charlemagne in 800AD.

The Florentine Petrarch’s love of the Roman Cicero and his mastery of Greek civilization sparked a new interest in humanism or self-culture. When in 1354 he discovered long lost copies of Cicero in the school library of Verona, a daughter house of Columban’s Abbey at Bobbio, the Italian Renaissance was born. Manuscript hunters collected the glories of Greek and Roman culture preserved by the scribes in Gaelic Christian Abbeys and a period of renewed interest in learning awakened in the wider culture.

The reacquisition of the knowledge of the ancients extended beyond letters, and when the manuscripts in the Abbeys revealed Aristotle, synthesizing ancient thought with Christian theology propelled a monumental change. A new scientific method advanced beyond past precedent and dogmatic certitude to reliance upon observation, reason, and the expectation of improvement and progress. Together this unprecedented and uniquely Christian worldview laid the foundation of the Scientific Revolution, beginning in 1543 with Copernicus’ publication of On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres.

Germany, Switzerland and Scotland had long been home to thousands of Gaelic Christian missionaries and hundreds of their Abbeys, the faith they celebrated and the culture they fostered. From these strongholds was launched the Protestant Reformation. Led by Luther nailing his 95 Theses to the door of Wittenburg Cathedral in 1517, Calvin’s preaching in Geneva, and Knox’s evangelizing in Scotland, the Protestant Reformation was inaugurated to revive holy living and free man from the tyranny of the Church. In Scotland, Knox established the reformed Church which was presbyterian in structure and Calvinist in doctrine. Members of the Church committed to a new Covenant with God, chiefly, that Christ is the only King, his Church subject only to God, and all members ruled by those elected from among equals, presbyteries of ministers and elders.

Similarly, beginning around 1715, the Scottish Enlightenment saw a period of new thinking grounded in rational religion. This approach, inspired by ancient Gaelic clan and Christian traditions of independence and self-governance, sought to discern the will of God in all things, reviving virtuous living and freeing man from the tyranny of State. From the beginning Gaelic Abbeys had practiced presbyterian rule with Abbotts and Abbesses elected from a community of equals – rule by the consent of the governed.

It was Scotsman James Watt, son of strong Presbyterian Covenanters, that invented the improvements to the steam engine in 1765 that launched the Industrial Revolution and Church of Scotland member Adam Smith, professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow, who published On the Wealth of Nations in 1776. Simply, the far reaching impact of the Industrial Revolution’s mechanization of production combined with free market capitalism and driven by Christian work ethic is still improving lives all around the world. Today, Smith is known alternately as The Father of Economics or the Father of Capitalism. The University of Glasgow, it will be remembered, is one of the ancient universities born in a direct line from the teaching programs of the scholastics of Gaelic Abbey schools.

Of course, 1776 is also the year of the American Declaration of Independence, among the greatest achievements of humanity. In 1978 Gary Wills wrote Inventing America stating “the Declaration, . . can be properly understood only if it is analyzed as a product of the Scottish Enlightenment, and that Jefferson’s views on the nature of man and society derived . . . from the works of (Scottish philosophers) Thomas Reid, David Hume, Adam Smith, Lord Kames, Adam Ferguson, and Francis Hutcheson.”

Finally, the Constitution of the United States was ratified in 1788. The principal framers and advocates were all products of the Scottish Enlightenment based upon ancient Gaelic clan and Abbey traditions of Christian virtue, independence and republican self-governance. James Madison is recognized as the Father of the Constitution, and he was educated by a Scottish tutor and then under Scottish Presbyterian minister, University of Edinburgh graduate and President of the College of New Jersey (Princeton) John Witherspoon. James Wilson is second only to Madison in influence on the Constitution, and he was a Scotsman, educated at the Universities of St. Andrews, Glasgow and Edinburgh. Alexander Hamilton was the principal author of the Federalist Papers, with Madison, advocating for ratification, himself a Scotsman graduated from Kings College (Columbia). These men created a republican government with the promise of political, economic and religious freedoms – ideals originated among Gaelic Christian Clans, incubated in the Gaelic Christian Family Abbeys and spread far and wide as Western Christian Civilization, inspired by God, man’s greatest gift to mankind.

Scotus

Marguerite Dubois. Saint Columbanus, Irish Monks in the Golden Age, John Ryan, ed, 1963

Daniel Rops, Saint Columban and his Disciples, The Miricle of Ireland, 1959

Heinrich Zimmer, The Irish Element in Medieval Culture, 1891

James Clark, The Abbey of St. Gall As a Centre of Literature & Art.. 1926.

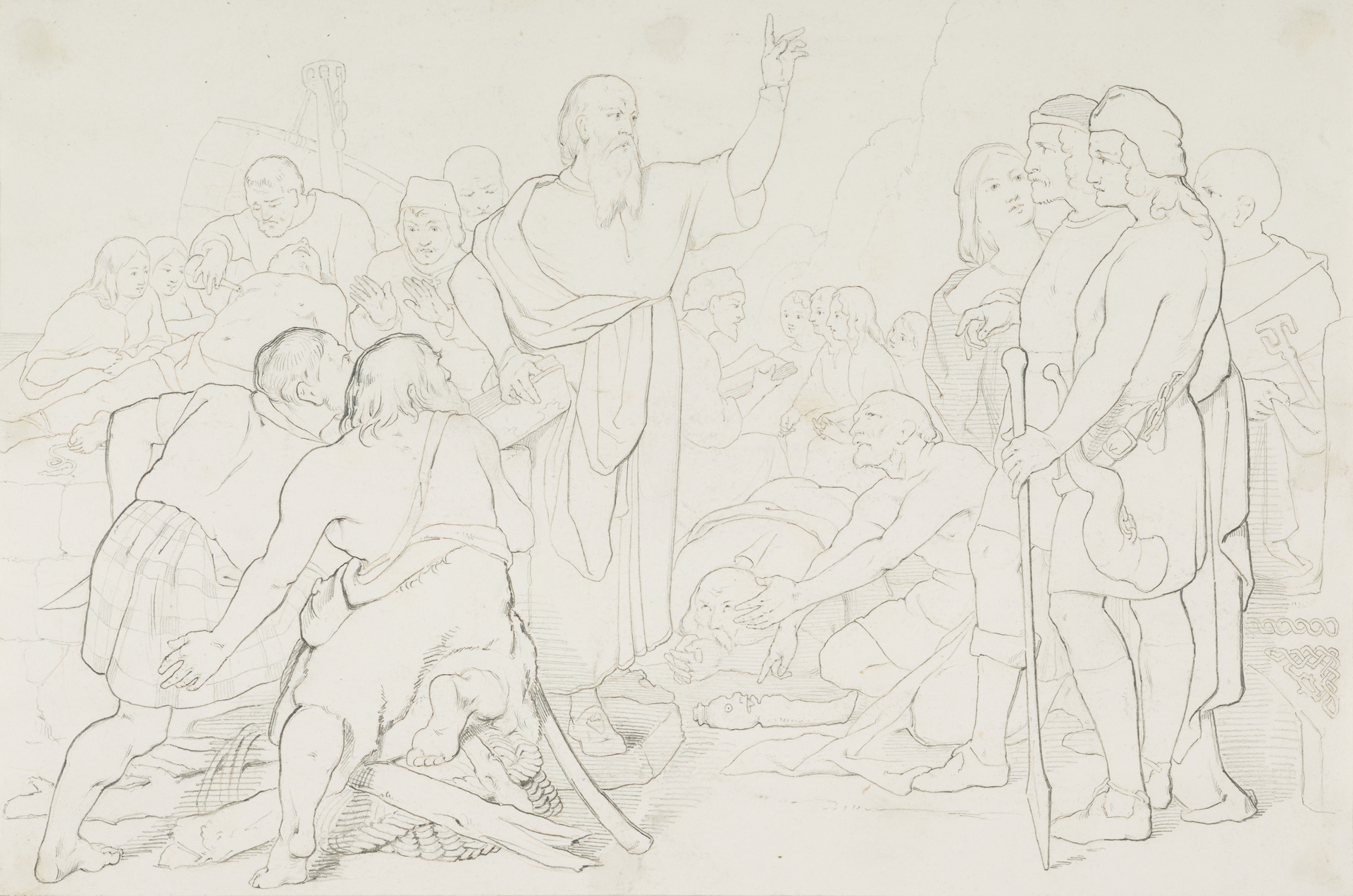

photo credit: Saint Columba Preaching, William Bell Scott, National Galleries of Scotland