Consent of the Governed: Ancient Family Antecedents

Consent of the Governed: Ancient Family Antecedents

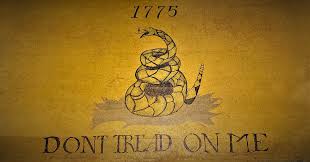

“Don’t Tread on Me” read the flag of the protester outside the Virginia State Capitol, May 2020. Emblematic of the original Gadsden Flag from the American Revolution, it conveyed the American patriotic virtue of rebellion against tyranny. The Governor had declared a State of Emergency March 21 and locked down the State. Now past two months later, citizens were questioning his authority and motivation. Twenty-five of our United States limit their Governors’ authority in such cases, most to from 15 to 30 days. Entering the 3rd month of the State shutdown, citizens were questioning the Governors’s authority to rule by decree with no consideration of the views of the people. How could this stand?

“No Taxation without Representation” we also recall as a rallying cry of colonial America against the tyranny of England. For more than 100 years Parliament had controlled trade and levied taxes on the Colonies and by 1760 many in Colonial America believed they were being deprived their civil rights as Englishmen. How could honest government legitimately regulate and tax a populace who had no say in the matter? These issues, among others, eventually led to Americans fighting and winning the War for Independence.

Some historians wonder why the British did not practice “Taxation with Representation” and even Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith among a few others advocated for direct colonial representation in Parliament. Galiani & Torrens argue in a 2018 NBER paper that elites in England feared “a strong Colonial faction in Parliament would disrupt their ruling bloc and a fight to retain power was in any case unavoidable.”

The question about the legitimate power of governments over men is ancient, going back to the first family member who asked, “Why do we have to do what he says?” Usually rule was due to established family lineage or military might.

With the Bible originated the idea that all men are created equal, which introduced new rationale for questioning the legitimate power of one man’s authority over others. When Jesus said “Render unto Caesar . . .” in the synoptic gospels, potentates from Popes to Kings rationalized their right to be first among equals, divinely appointed by God to guide and protect His children on Earth. The divine right of Kings thereafter became a point of contention. Jeff Barr for the Mises Institute offers an engaging essay assigning tribute to the “subtle sedition” of Jesus.

The divine right of Kings was eventually successfully challenged and to unpack that development we must review some Gaelic-Scottish History. When Julius Caesar arrived in Gaul in 58BC he encountered, along with the many and varied barbarian tribes, a spiritual sect known as Druids. Caesar wrote in the Gallic Wars that the Druids on the Continent looked north across the channel for the home of their practices and when he crossed to Britannia in 55BC he discovered that truth. More, archeology displays a counter-intuitive yet marked North-to-South cultural progression as evidenced by, among many other things, the Stone Circles in Britain. The Clan Legacy reveals that with the Stenness stones of Neolithic Orkney dating from 3,100 BC,

“The complex is dated 500 years before the Great Pyramids of Giza and 1,000 years before Stonehenge. In its dedication in 1999, UNESCO recorded “the site illustrates the material standards, social structures, and ways of life of this dynamic period of pre-history, which gave rise to Avebury and Stonehenge in England, Bend of the Boyne in Ireland and Carnac in France.”

It is fair to say that the Neolithic spiritual culture of the British Isles originated with the Druids in the Gaelic north of Scotland.

Caesar, the oft self-servingly detailed anthropologist, also noted peculiar practices and beliefs of the Druids; specific to our review, their dedication to knowledge, belief in a soul with an after-life and their governance by an elder elected from among their group of equals. Of course from the receding of the last ice age the people of the region were Gaelic and socially organized in extended kinship groups called Clans, meaning children. The Clans were led by a Chief, according to their ancient tradition of tanistry, the elected first among equals. Given the Druidic pre-Christian spirituality of the Clans, we see here emerging from the mists of antiquity a people who organized their social and spiritual lives with leaders elected from groups practicing broad social, political and religious equality.

When the Gospel arrived in the British Isles in the fist century contemporary with the lives of the Apostles, it was received in Gaeldom with unprecedented enthusiasm. Whether it was the notion of the naturalism of creation, the salvation of the soul or God-given equality, Christianity adhered to the Gaels immediately and tenaciously. The Clan Legacy notes,

“French polymath Ernest Renan recognized the unique watershed in human history. In his 1896 Poetry of the Celtic Races, he writes that the Gaels were “predestined to Christianity, naturally Christian” a faith that “finished and perfected them,” saying that “by the third century they were perfect Christians. Everywhere else Christianity found, as a first sub-stratum, Greek or Roman civilization. Here it found a virgin soil of a nature analogous to its own, and naturally prepared to receive it.”

Christianity eclipsed Druidism, and by the sixth century was flourishing within the monasteries and Abbeys of Gaeldom, chief among these Iona in Scotland and its daughter Abbey Lindisfarne in what would become England. Abbeys were typically founded and supported by a local Clan family, the Abbott most often an elected lay member of the Clan. In concert with the well known Clan castle bastions, Abbeys served the faith and family for numerous generations, while emerging as vital centers of culture, commerce and civilization. Scottish Presbyterianism emerged from these cultural and faith traditions, among other things characterized by church administration on a local basis through elected equals of lay congregants called presbyters. Gaelic Christian traditions from the first held for liberty from outside influence, equality and elected leadership. And history provides this evidence. As Bede records in his History, citing Pope Gregory’s libellus responsionum, in the 602 AD first meeting of the Gaelic Christians with Augustine’s Catholic missionaries sent from Rome by Gregory, the Gaelic Christian fathers said they could not accept the Roman’s demands for submission to Papal authority without first discussing the matter and obtaining the consent of their people. Further, Yorke writes in The Conversion of Britain that Augustine was frustrated in his attempts at coerced consolidation by the fact that the Gaelic Church was not a monolithic institution but rather an association of numerous independent local communities.

In native form, Liberty introduces the natural tension between order and chaos – the freedom of one in conflict against the rights of another. Early Gaelic traditions reconciled these issues to manage the tension for the successful development of family, church, community and culture. The historical source for reasonably articulating a system of self governance is Scotsman John Duns Scotus. In his Ordinatio, published in 1290, he recorded his lectures – questions asked and answers delivered – during his professorship at Oxford University. Duns Scotus detailed original statements on the theory of sovereignty and the social contract centuries before more well known philosophers Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau. The ideas of Scotus form the original foundation of modern political theory. His statements on human society, carried forward from ancient Gaelic culture tempered by time, revolutionized contemporary thought and practice, providing the rational intellectual justification for advance in Scotland, Great Britain and eventually the United States of American and indeed, all of Western Civilization. To that point, historian Richard Brookhiser said in a 2020 Law and Liberty interview that “you can look at the history of the world and see it as a struggle for self rule.”

As Professor Harris wrote in 1929, “Scotus is important in the history of political science as one of the pioneers of modern social theory. His doctrines on social contracts . . . precede . . . the later teachings of Locke. Scotus’ account of the social contract is a philosophical analysis of the origin of society. Society, he held, was naturally organized into family groups; but when paternal authority was unable to enforce order, political authority was constituted by the people. Accordingly, all political authority is derived from the family by consent of the governed.” We see that the Gael Duns Scotus found the original mediating authority between the rights of free men within the family, and when the issues or egos exceeded the head of the family, then authority was held by the larger community of political equals. Unconstrained liberty moderated by the head of the family, then by the community through the consent of the governed.

Still, Kings sought to assert their “rights” when and where possible. On this matter, and in particular to Scotland’s plight, Alex Oliver, attributing Scotus declared, “The real root of royal authority had nothing to do with inheritance. A king whose power was legitimate was king because his people granted him their consent, and if that consent were to be withdrawn for any reason then the man was king no more.”

And the teaching of Scotus catalyzed thoughts, words and deeds. Scotland’s great warlords William Wallace and Robert the Bruce led her long terrible fight for independence. And the Scottish church too continued to demand self-governance. In the 1320 Treaty of Arbroath, fighting churchmen, especially William Lamberton echoed the words of Scotus, whom he had met in Paris, authoring the immortal words (emphasis this writer),

“his right of succession according to our laws and customs which we shall maintain to the death, and the due consent and assent of us all, have made our Prince and King. To him, we are bound both by law and by his merits that our freedom may be still maintained, yet if after all, if this prince (King Robert) shall leave those principles which he hath so nobly pursued, and consent that we or our kingdom be subjected to the king or people of England, we will immediately endeavor to expel him as our enemy, and as the subverter of both his own and our rights, and will choose another king who will defend our liberties. For as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, none will on any conditions be brought under English rule. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honors that we are fighting, but for freedom – for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.”

In Scotland, so long as the King by his reign retained the approval and consent of the people, save for battle, he might be able to die in his bed. Quoting again from The Clan Legacy,

“Recognized as Scotland’s preeminent intellectual of the 16th Century, George Buchanan was tutor to King James, who later produced the incomparable Bible that bears his name, and was a leader of the Scottish Reformation. He also asserted a “contractual nature of monarchy” that provided for citizen’s rights to remove the Prince, a direct assault on the historical divine right of Kings. Scots were the first in history to reject the right of the King, or anyone else, to violate their freedoms, long before the Enlightenment. A logical extension of rule only-by-consent pertained to taxation. No taxation without representation, a rallying cry of the American Revolution, saw direct parallels in prior Scottish experience first with the Highlanders at James’ Union of the Crowns in 1603 and then for all of Scotland at the Act of Union in 1707.

So, government by consent was long practiced in Greater Gaeldom and Scotland, culturally, religiously and politically and saw philosophical exposition in the writing of Duns Scotus, the appeal of the Treaty of Arboath and the work of intellectuals like George Buchanan. Indeed the Scottish Church fought fiercely for its independence, first from Rome and then from London. History records the 644 Synod of Whitby when the Roman Catholics subdued the Gaelic Christians in the contest for the soul of England. Centuries later the rallying cry of “No Bishop! No King!” went forth from freedom loving people on both sides of the Atlantic. Of course, this concept was at the forefront of the thinking of the Scottish Colonists and their educated peers and of paramount importance in the drafting of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.”

The United States Declaration of Independence

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness –That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, –That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

In a miracle of symbiosis among Gaelic first principles, liberty led to literacy and literacy led to expanded liberty. The liberty of Man proclaimed by the Bible led to personal, religious, political and commercial freedoms. The translation of the Bible into English combined with the invention of the printing press to catalyze the rapid rise in literacy of the English speaking world. Particularly in Scotland, by 1560 the Reformed Presbyterian Church led by John Knox carried forward ancient Abbey school traditions with a program of free parish schooling that soon saw the Scots become the most literate population in the world. It might be noted that Scotland had four universities at St. Andrews, Glasgow, Aberdeen and Edinburgh, England only two. People learned to read and write to study the Bible for themselves and share their understandings. Primary among those understanding was that Jesus came to set men free, free from the tyranny of Church or State. Further, the worldwide sacrifices of Gaelic missionaries to learn, document and translate foreign languages into English, and the Bible into those foreign languages, brought literacy, advance and the power of the Bible and its unalienable rights around the world.

Today our Constitutional Democratic Republic is the original and unique model for self-governance, as human liberty, freedom and equality under law unleashed the greatest rise in the global human condition in world in history. Our American model is also to be honored for what it has not done. Recall that two other revolutions for independence were fought contemporarily with ours, that of France beginning 1789 and Haiti later in 1791. They were both long bloody affairs with appalling atrocities on both sides and conclusions which only saw the continuation of tyranny and oppression.

The French Revolution is marked by the Reign of Terror during 1793 in which near 17,000 political opponents of the Provisional Government’s Committee of Public Safety, were sent to the guillotine. During some peak periods there were as many as 90 public political beheadings a day. The following 100 year history of France is more generally well known, though not for traditions of stable democracy or individual liberty. In Haiti, seeking solidarity with the uprising in France, 500,000 black slaves revolted against 32,000 white French colonists, soon reinforced by Napoleon’s 40,000 man army. After 12 years of bitter struggle the rebel slaves under Jean-Jaques Dessalines won independence. In The Slaves that Defeated Napoleon, Phillipe Girard recorded Dessaline’s secretary stating, “For our declaration of independence, we should have the skin of the white man for parchment, his skull for an inkwell, his blood for ink and a bayonet for a pen!” In consolidating his new government, Dessalines ordered the comprehensive massacre of almost 5,000 unarmed civilians of both sexes and all ages. Haiti’s Constitution of 1805 declared that all citizens were to be declared “black” and banned others from owning land. In the new independent Haiti Dessalines was declared Emperor, serving for two years before his assassination in 1806 by his Generals. The episode of the slave revolt and eventual massacre of whites reverberated long in the Unites States, a head wind against abolition until the Emancipation Proclamation and Northern victory, indeed perhaps fueling racist fears in some quarters to this day.

In the long broad tapestry that is human history only very few threads weave together strands of self-determination, freedom and progress. Only one is visible connecting continuously and brilliantly from the dawn of recorded history to the prevailing glory of the United States of America. Are there family traditions more important to celebrate? Has there been a better example than rule by the consent of the governed, for the betterment of the world? Are we to celebrate the rule of law or succumb to the rule of Man?

Scotus

Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico, (Gallic Wars), 49 BC

C.R.S. Harris, Duns Scotus, Oxford University Press, 1927

Bruce M. Goedde, Jr., The Clan Legacy: Essential Family Capital Stewardship Strategies for the Next 1,000 Years, 2018

Neil Oliver, A History of Scotland.’ Phoenix: London, UK. 2010.

Harris on Scotus 1929

photo credit: Gadsden Flag, Rob Hans, 2018