Why Abbeys? The Mission of Icolmkill House: Part II – The Abbey in its Glory

Why Abbeys? The Mission of Icolmkill House: Part II – The Abbey in its Glory

The Gaelic Christian Family Abbeys emerged as near comprehensive incubators for civilization. Born as they were in illiterate pagan barbarian lands as islands of Christian lifestyle, they were by nature self-reliant in their worldview and self-sufficient in the planning and conduct of their affairs. Dedicated to Christ honoring thoughts, words and deeds, they embraced an attitude of progress and promoted execution to the highest standards, eventually establishing the state-of-the-art across virtually every field of human endeavor. It’s been said the Abbeys were crucibles of holy living and cultivation of the mind. It is the great gift to the world that the Gaelic Christian Abbeys believed it their purpose to spread by example their faith and acquired knowledge first among their network of associated Abbeys, and from there to the wider world through their missions and establishment of daughter houses, fountains of civilization and stability.

Rodney Stark writes in The Victory of Reason, How Christianity Led to Freedom, Capitalism and Western Success, “Christian Commitment to Reason and Progress wasn’t all talk; soon after the Fall of Rome, it encouraged an era of extraordinary invention and innovation.” And most all this was centered in the Christian monasteries and abbeys. Continuing, Professor Stark explains, “the so-called Dark Ages (from the Fall of Rome until the Italian Renaissance) was an extraordinary outburst of innovation in both technology and culture. What was most remarkable was the way in which the full capacities of new technologies were rapidly recognized and widely adopted, as would be expected of a culture dominated by a Christian faith in progress. Nor was innovation limited to technology; there was remarkable progress in areas of high culture – such as literature, art and music – as well. Moreover, new technologies inspired new organizational and administrative forms culminating with the birth of capitalism within the great Christian monastic estates. These developments soon vaulted the West ahead of the rest of the world.”

Emmet Scott writes, “Although the monk’s purpose in retiring from the world was to cultivate a more disciplined spiritual life, in the end the monasteries would play a much wider and historically significant role. The monks may not have intended to make their communities into centers of learning, technology and economic progress, yet as time went on, this is exactly what they became. Indeed, one can scarcely find a single endeavor in the advancement of civilization during late antiquity and early middle ages in which the monks did not play a central role.”

It is well known of course that they preserved the literary inheritance of the ancient world, yet did so much more. In The Monastic Realm, the authors assert, “The whole of Europe a network of model factories, centers for breeding livestock, centers of scholarship, spiritual fervor, the art of living, readiness for social action, in a word – advanced civilization that emerged from the chaotic waves of surrounding barbarity.”

Let’s review just four broad areas of human progress catalyzed in the Gaelic Christian Family Abbeys the formed the foundation of modern Western Civilization:

Literacy & Education

Taken for granted in the West today, it is incredible to consider there was a time when very few people could read or write. Further complicating the advance of literacy was the multiplicity of languages. Greek was the language of the classical world loved by Romans. The literate administrative and military elites of the Empire used Latin, but the 50 million others spoke one of hundreds of local vernaculars communicated from Syria to Britain. To the extent that Latin was relied upon in the remote administrative and legionary centers of the Empire, it steadily departed from standards, became increasingly bastardized, eventually falling into disuse completely in the sub-Roman world.

Importantly, the Bible and the texts cherished and studied by the monks were written in the Aramaic of the Jews, the Greek of the Gentiles and the Latin of the early Church fathers. For the purpose of worship, especially acquiring knowledge of God’s revelation of his creation and will, the monks mastered reading and writing in those languages. Further, in addition to command of Christian writings, access to the classical languages also revealed the secular wisdom of the ancients. Through language, the monks of the Gaelic Christian Abbeys ‘acquired the collected knowledge of the ancients’ and through inspiration and diligence became the most well educated people in the world. Combined with knowledge, curiosity and faith in discovery and improvement propelled the Abbey communities forward.

Every Abbey featured a school, where not only the monks, but every person ‘seeking knowledge’ was welcome to study. An amazing ecosystem of advance was established. The acquisition of knowledge required parchments, manuscripts and books so the Abbeys and their far flung missionaries became zealous collectors of every kind of writing from every part of the Western world. Libraries were developed to catalog and store the manuscripts, and scriptoria created to translate and copy all for preservation and wider distribution. The expanding size and number of schools required learning materials further accentuating the value of the labors of the scriptoria and libraries. Missionaries and other Abbeys created further need for translation, copying and production. The great majority of the literature of Greece and Rome that has survived to modern times was collected and preserved by Gaelic Christian monks in the sixth the seventh centuries. Alcuin was known to lead the best library in Christendom at York, with works by Aristotle, Cicero, Lucan, Pliny, Statius, Virgil, Ovid, Horace and more.

Critically, the monks of the Abbeys rationalized language to propel literacy and education forward. First, they created Latin grammars to standardize and purify the language for teaching to non-Latin speakers. Next they created alphabets and lexicons for the reading and writing of the local language, followed by local-to-Latin and Latin-to-local teaching aids. Language delivered the tool for literacy and literacy for education and the acquisition of knowledge. Finally, literacy allowed for development of common culture based upon language, and the administration of the society through land titles, pronouncements, commercial contracts and other forms of official communication. The populace was motivated toward literacy for personal improvement, social and cultural participation. Perhaps the greatest incentive was acquiring the word of God for personal spiritual enlightenment and growth.

With a school at every Gaelic Abbey and an inspired drive for language, literacy, learning and knowledge, the success of the model was acknowledged and adopted by the Catholic Church and soon every cathedral too had its school. A new system of thought was developed in the Abbey schools, exemplified by John Scotus Eriugena, the giant of Western intellectual tradition who synthesized the philosophy of twenty centuries, from ancient Greece with the Christian theology, logic and rationality. There is a direct line from the Gaelic Abbeys to the Benedictine Abbeys and the Cathedral schools to the advent of the ancient Universities, unique in all the world. There, Christian scholars, scholastics, gave rise to science and used reason to ignite advance. In Scribes and Scholars, the authors state “if they were classical scholars, they were also adventurers in advancing every field of knowledge – natural philosophers, engineers and agriculturalists, medicine, painting, calligraphy, music, engraving, teachers, grammaraticians, philosophy, astronomy, metal working, stone building and architecture.” It was the Gaelic Christian Family Abbeys that brought literacy and learning to an ignorant world, and faithful Christian civilization to pagan barbarity.

Practical & Creative Arts

Before Christianity, physical labor was shunned as fit only for the subsistence and slave ranks. It was our faith that dignified work, forming a foundation for a middle class and a fulfilling future for free people. Christians viewed work as both practically and spiritually rewarding, as modeling the humble examples of Christ the carpenter, Peter the fisherman and Paul the tentmaker, while celebrating creativity in man, the creation of God the creator. In keeping with monastic dedication to self-reliance and self-sufficiency, the Abbeys created everything they needed, and their dedication to reason, practical diligence and frugality led to surplus, prosperity and expanding charity.

The monks of the Abbeys made busy with every kind of productive activity known to man, and then improved upon them and invented new ones. They excelled at agriculture, herd management, fish farming, raising bees, brewing and distilling, weaving cloth, cultivating orchards and tanning leather. We find a monastic origin for many foodstuffs, especially the wide varieties of cheese, given the large herds of goats, sheep and cattle. Sheep were prized and ubiquitous among the Abbeys, the source of milk, butter, cheese, meat, skins for parchment and especially wool for garments. Among important innovations were water and wind mills to enhance productive energy; the horse collar allowed a switch from oxen to horses for plowing; the moldboard plow turned fields over to deepen plantings and enhance crop vitality; greater yields allowed for a rotating three field system with one set aside for grazing, the manure fertilizer from the herds enhanced soil quality. Christian Abbeys were responsible for the great improvements in the making of beer, wine and spirits. Wine beheld Biblical references and Abbeys naturally cultivated orchards and vineyards for the beverage, used in liturgies, an everyday drink, as a medicinal and for cash at market. Though beer was popular and widely available, hops was first added at Corbie Abbey and brewing at scale for commerce an innovation of the Abbeys. Munich, capital of Bavaria and beer in Germany means ‘home of the monks.’ Whiskey was first widely distilled in the Gaelic Abbeys and when the process carried to the continent fruited brandies were born. Today, many of the discreet historical styles, regions and appellations of alcoholic beverage production originated around Abbeys.

As metal workers the Abbey monks produced tools, kitchen and dining ware, hoops for barrels and hinges and latches for doors and windows. Cloth making became widespread and led to the establishment of the textile industries. The monks excelled at architecture and building, developing many of the techniques that culminated in the great Christian churches and cathedrals. All these innovations of the Abbeys greatly expanded productivity and quality of life and were readily reciprocally distributed widely throughout the network of Abbeys and their neighboring settlements.

Through agriculture, new crops and new techniques, the Abbeys brought Europe into cultivation and land value, sustaining populations and civilization. Typical of laudatory acknowledgments “Wherever they came, they converted the wilderness into cultivated country; they pursued the breeding of sheep and goats and cattle, agriculture, labored with their own hands, drained morasses, and cleared away forests, rendering fruitful country.” Their inventiveness and innovation was distributed across the network of Abbeys and expanding surrounding settlements.

Along with improving the quality of life, Abbeys were pioneers in treating the unavoidable illness, infirmity and end of life episodes of Man with hospitals and hospices. In his book Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals author Gunter Risse writes, “Following the fall of the Roman Empire, monasteries gradually became the providers of organized medical care not available elsewhere for several centuries. Given their organization and location, these institutions were virtual oases of order, piety, and stability in which healing could flourish. To provide these caregiving practices, monasteries also became sites of medical learning between the fifth and tenth centuries, a period of so-called monastic medicine, especially the study and transmission of ancient medical texts.” Concern for the human body led to the study of physiology, pathology and useful medications. Experimenting with plants and herbs advanced ideas about biology and botany. The Abbeys offered free care to the needy, an unprecedented advance with nothing like it ever before in the pagan world.

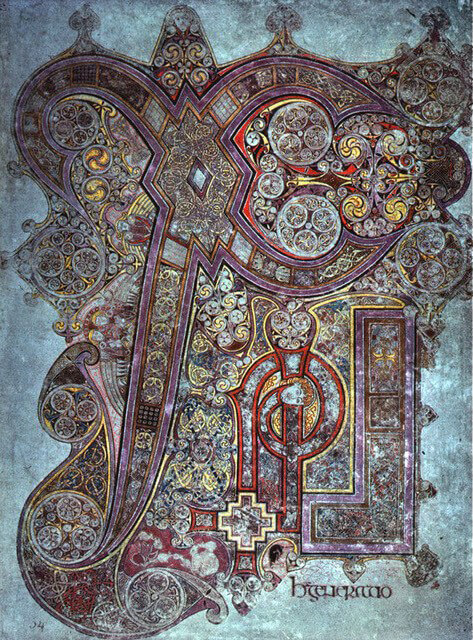

The creative arts experienced a period of growth and achievement that astounds experts to this day. In every medium – wood, stone, metal, calligraphy, manuscript illustration, music, literature – the monks of the Gaelic Christian Abbeys created works of art that are par execellence for the discipline and among the treasures of the Western World. In just a few examples, consider the incomparable contributions from the 6th through the 9th centuries: the stained glass windows of the great Christian churches and cathedrals, originated at Monkwearmouth Jarrow; the illuminated manuscripts like the Gospel of Columba (Book of Kells) originated at Lindisfarne and Iona; the Ardagh Chalice of silver and gold; the precious peninsular Tara Brooch; the stone high crosses originated at Iona; the Carolingian script of St. Gall or the musical scale, acoustic instruments and monastic chants of Corbie.

Already by 1007, the Annals of Ulster proclaimed the Gospel of Columba to be “the chief relic of the western world.” Aleska Vuckovic’s article calls the Book of Kells “An Immortal Cultural Heritage of the Gaels.” It is characteristic of the Gaelic monks that one of the sublime artistic expressions from the codex is the Chi Rho carpet page, glorifying the first two letters of the name Christ, in Greek.

The insular art of the Gaels was unique, a fundamental departure from classical approaches to decoration, in particular the intricate interlace patterns, whimsical figures and fantastic creatures. The tradition can be traced back to 3rd century Pictish standing stones, and is thought to have advanced from earlier woodworking, to stone and to precious metals and then vellum. The complexity of insular decoration inspires wonder and deep reflection, and perhaps was designed to induce a meditative state appropriate for worship. Richard, a 12th century Scottish prior of the Abbey of St. Victor in Paris, called consideration of the work an “ecstatic contemplative experience.” According to experts, the Insular style of Gaelic artists produced an enormous achievement that greatly influenced and gave rise to all subsequent European artistic traditions especially Romanesque and Gothic.

The artistic contribution of the Gaelic Christian Family Abbeys is all the more remarkable when we remember that virtually every one was assaulted, sacked and burned by Norse marauders beginning in 793AD at Lindisfarne. The monks were murdered or enslaved, the treasures stolen and the libraries, scriptoria and storehouses burned, effectively concluding the Insular creative period. Many treasures of great renown only survive today following their rediscovery in places of hiding from the Vikings. The Gospel of Columba is today known as the Book of Kells because it was relocated from Iona to Kells in response to Norse depradations. One wonders what other exemplars might have endured, or yet been created, if not for the wonton murder and destruction by illiterate pagan barbarians.

Commerce & Capitalism

We look to the Gaelic Christian Family Abbeys as the genesis, incubator and catalyst of the Earthly Trinity blessing America since her founding: Christianity, Capitalism and Republican Democracy. We have discussed elsewhere (paxfutura.org) how Prosperity is downstream from Christianity, and dependent upon Christian virtues of freedom, independence and private property. We noted that greater Gaeldom was never part of the Roman experience, and innovation, invention and improvement only make sense where property is safe from seizure with benefits accruing to the creators. Further, once advance from subsistence was achieved, the focus of the Abbeys became consistent with that of their clan sponsors – continuity. According to Stark, “Capitalism evolved beginning early in the ninth century by monks who despite having put aside worldly things, were seeking to ensure the economic security of their monastic estates.”

In the nascent environment of free markets, private property and free labor, the Gaelic Christian Abbeys developed an engine of economic advance, self-reliant in outlook and self-sustaining in practice. The Christian ethic of the virtues of reason, work and frugality led to reliable surplus, generally unheard of in all prior times. The surplus of the Abbeys was directed toward expanded charitable care for the needy, support of local communities and gain at market. The profits were then available for reinvestment in the Abbey operations and projects, and eventually for loan at interest. In this way, the Abbeys created a commercial ecosystem that evolved from barter to cash, and from direct exchange to credit and banking. Eventually the Abbeys became large land owners through purchase and gifts, with extensive networks of associated communities, many had forty of fifty daughter houses and were very liquid in material wealth, especially in artistic treasures both created and donated. Surrounding the Abbeys settlements grew into towns, trade networks developed and flourished as the commercial activity scaled and was strengthened through expanding association.

Writing of the great Gaelic Christian Abbey of St. Gall, Christopher Dawson noted “it was no longer a simple religious community, envisaged by the old monastic rules, but a vast complex of buildings, churches, workshops, store-houses, offices, schools and alms houses housing a whole population of dependents, workers and servants like the the temple cities of antiquity.” As the Abbey activities grew in complexity specialization increased and as they grew in economic wealth, management became a priority. Here the Abbeys benefitted from the monastic meritocracy where talent, education and leadership was prioritized in the interest of developing and executing plans for very long duration.

Historian Randall Collins called the advance of commercial capability and commitment of the Abbeys ‘religious capitalism.’ As the estates of the Abbeys and monasteries developed productivity gains, they propelled a shift from barter to cash, established management, the specialization and distribution of labor, accounting, trade terms and networks, credit, lending, investment and the creation of wealth. This wealth, in the form of Capital, was discovered to have the capacity to be put to work to return income – the use of wealth to earn an increase in wealth. Similarly, the monks pioneered Investment, or the systematic risking of wealth with third parties in pursuit of gain, targeted toward productive activities where new wealth is created.

Capitalism, according to Stark, was invented within the monastic estates and defines an economic system wherein “privately owned, relatively well organized and stable firms pursue complex commercial activities within a relatively free market taking a systematic, long-term approach to investing and reinvesting wealth in productive activities involving a freely contracted workforce and guided by anticipated and actual returns.” Eventually, the Abbeys, as the originators of cash, credit, lending and investment, became banks serving the populace from the ranks of royalty down to the rent payer.

Let’s not forget that the Abbeys were founded, underwritten and directed by the sons and daughters of prominent local families. In their glory, the Abbeys were stable springboards for the spread of sustaining settlements, our Culture and Civilization, the Light and Envy of the World. Is there a better example today for Christian families seeking to establish multi-generational legacies for themselves and as gifts to all God’s children in expanding His Kingdom?

Scotus

Rodney Stark, The Victory of Reason: How Christianity Led to Freedom, Capitalism, and Western Success, 2005

Emmet Scott, Mohammed & Charlemagne Revisited, The History of a Controversy, 2012

Gunter Risse, Mending Bodies & Saving Souls, A History of Hospitals, 1999

Aleska Vukovic, The Book of Kells: The Immortal Cultural Heritage of the Gaels, 2019

Christopher Dawson, The Making of Europe, 1932

photo credit: Chi Rho Carpet Page, Gospel of Columba (Book of Kells)