One Nation Under God

One Nation Under God

‘One Nation Under God’ is part of the Pledge of Allegiance of the Unites States of America, adopted by a joint resolution of Congress amending our Federal Flag Code on June 14, 1954. Along with many other American traditions, the phrase has come under attack. Princeton Professor Kevin Kruse published “One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America” in 2016, his title perhaps foreshadowing his point of view. The main thrust is that the phrase ‘One Nation Under God’ was not part of the Pledge until 1954, in support of the Professor’s view that the idea that America is a Christian nation is an invention of Christian business interests 178 years after-the-fact.

There are three main explanations for what would be the Christians’ considered 1954 creativity. One posited that conservative Christian businessmen desired to obstruct the further advance of FDR’s New Deal assaults on unbridled capitalism, positioning free enterprise as heavenly blessed. A second suggests that President Eisenhower drove the initiative, his recent baptism as a Presbyterian catalyzing his vision for a new conception of a Christian America and the necessity of its rigorous installation into public life. Another consideration was that determining America to be Christian presented a Cold War visage to the world differentiated from that of the state atheism of Russian and China. Before dismissing the legitimacy of the traditional understanding of ’One Nation Under God’ it may profit us to take a closer look at its origin and meaning.

What is a nation? According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a nation is “a large body of people united by common descent, history, culture, or language, inhabiting a particular country or territory.” Until very recently, America was by any analysis a nation. We were indeed a large body of people most distinguished by common history, culture, language and territory. Yet what has changed? Certainly not any of our history, culture, civil language or territory, but rather definitions and understandings about what those long-held characteristics of America mean.

We are now told by our newspaper of record The New York Times that America was not founded in 1776 by our Declaration of Independence, but in 1619, upon the arrival of a slave ship to Virginia, and that the American War for Independence was fought to perpetuate the institution of slavery. We are instructed that far from an exceptional model for the world of freedom, equality, opportunity and charity our culture is a toxic intersection of patriarchal white supremacy, systemic racism and prejudice against . . . well everything: sex, social class, political view, skin color, age, body shape – you name it. American is no longer a culture to celebrate and emulate but one to denigrate and target with grievances.

Though our Founders did not declare English as our official language on the Federal level, 31 States have decided upon English, and the language has long been the de facto language of the nation. According to a 2013 Harvard Business Review article by Christopher McCormick, “Countries with Better English Have Better Economies,” “proficiency with spoken English is linked to higher incomes and standards of living.” Generations of immigrants studied to learn English to identify as and assimilate with Americans and opportunity. No longer. According to Liberty Language Services, the Census Survey 2018 identified 67.3 million US residents that speak a language other than English at home, a number that has tripled since 1980 and more than doubled since 1990. Further, more than half of our Nation’s youth characterized as Generation Z are ethnic minorities. Spanish is the language most utilized as an alternative to English, representing in California, Texas and New Mexico (45%), (36%) and (34%) of speakers respectively.

It’s true that the common territory of America has not changed since the Gadsden Purchase fixed the current borders of the contiguous United States in 1854. But the open border policy of the last two generations has drastically changed the original group of people occupying the land that comprised the American nation. Official estimates place the number of foreign born people living the United States at 45 million, the largest number of immigrants in the world and nearly 15% of the population. Indeed, changes are reflected in the demographic age and race, challenges to traditional American history, culture and language that bring into question the very notion of nation.

If America was once a nation united about common history, culture, language and territory, it seems now to increasingly defy that description. Is there a unifying solution? Is there a post-national identity available to us? If not nationalism, is it predetermined to be globalism?

And what of the notion that America is a nation Under God? Though Professor Kruse stipulates that America was never a Christian nation, the very idea an invention of Christians late in 1954, there is support for another viewpoint. There is biblical imagery in the Book of Ezekiel written about 580BC of a New Jerusalem, the City on the hill of the Temple Mount – a new Nation Under God. Ezekiel is one of the Bible’s Prophetic Books, centered in a time of the fall of Jerusalem, exile to Babylon and prophesy about restoration and hope for the nation of Israel.

The Gospel of Matthew is commonly considered by scholars to have been written by the Apostle between 70 and 90AD. Following the Beatitudes in the Sermon on the Mount, in Matthew 5:14-16 Jesus teaches, “You are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hidden. Nor do they light a lamp and put it under a basket, but on a lampstand, and it gives light to all who are in the house. Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works and glorify your Father in heaven.”

This passage is commonly interpreted as Jesus teaching on morality and discipleship, morality the practice of considered Christian values and discipleship following Jesus in living and teaching of those values. The connection to the living and teaching of Christian values as a city on a hill was settled upon by John Winthrop’s sermon to Puritan colonists setting sail from England for Massachusetts Bay in 1630 titled, “A Model of Christian Charity.” Dan Rogers wrote in 2018 that Winthrop delivered a warning to his fellow colonists that “God and their enemies would be watching if they failed to uphold their covenant: “we shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us.”

University of Wisconsin Professor of History Paul Boyer writes, “The Puritans are a really interesting group in history, because they really saw the prophecies of great blessings to the ancient Israelites applying to themselves; coming out of the intensely apocalyptic political climate in England, in their own day, they see now the possibility of literally creating, in what they saw as a new and empty world, a truly righteous nation in New England. In Puritan sermonizing there’s the vision of the New Jerusalem, the city on a hill. So when the Puritans arrived on the shores of New England, they viewed themselves as a shining example to the rest of the world.”

Thereafter, Squires wrote in 2018 that “City on a Hill” came into use in American politics to refer to a religious America acting as a “beacon of hope” for the world, a nation of discipleship reaching to all under God’s morality. In the Spring 2020 Word & World, America as New Jerusalem, Christopher Richman wrote, “the notion of America as New Jerusalem appears in every genre and style imaginable: poetry, songs, presidential speeches, novels, political pamphlets, sermons and academic writings. It has been a powerful force in American self-understanding and motivation.”

And so it was, as President Abraham Lincoln’s historic Gettysburg Address offered, that “this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom . . .” Over the following years, there were several efforts to insert ‘under God’ into the pledge by groups ranging from the Daughters and Sons of the American Revolution to the Knights of Columbus.

Prior to the 1954 addition of ‘under God’ the Pledge read, “I pledge allegiance to the flag, of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

Further to the understanding of President Eisenhower’s role in adding ‘under God’ is the story of Reverend George M. Docherty, a Presbyterian Minister from Glasgow Scotland. Graduating from Glasgow University and training at Aberdeen’s North Kirk, in 1950 Reverend Docherty ascended to the pastorship of the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington DC. A century prior this Church had been the favorite of President Lincoln and tradition held that succeeding Presidents visit on the Sunday closest to Lincoln’s birthday and situate in the very pew subscribed by him.

President Eisenhower was in attendance on Lincoln Sunday February 7, 1954 and Reverend Docherty preached a sermon titled “A New Birth of Freedom” advocating that ‘under God’ become a part of the Pledge. Docherty had previously sermonized about the need to insert ‘under God’ into the pledge, but this sermon proved propitious with President Dwight D. Eisenhower in attendance. According to a later 2004 Associated Press interview, “Docherty himself had not heard the Pledge of Allegiance until he heard his young son recite it. ‘I came from Scotland, where we said ‘God save our Gracious Queen,’ and ‘God save our gracious king,’ “Here was the pledge of allegiance, and God wasn’t in it at all.” “To omit the words ‘under God’ in the Pledge of Allegiance is to omit the definitive factor in the American way of life,” Docherty said from the pulpit. “The definitive factor in the American way of life.” Did the good Scottish minister have solid grounds for this firmly held belief?

Though a matter of much debate today with objections from historians, civil libertarians and atheists, there is solid evidence that God is the definitive factor in the American way of life

God is freedom which led to our unprecedented and definitive Declaration of Independence;

God is equality which led to our unprecedented and definitive free market economy;

God is love which led to our unprecedented and definitive brotherhood and charity at home and abroad;

God is reason which led to our unprecedented and definitive advance of the human condition;

God is morality which led to our unprecedented and definitive sense and system of justice;

God is forgiveness which led to our unprecedented and definitive rehabilitation of relations among individuals, families, communities and nations underwriting improvement and advance around the world; and,

God is grace which led to our unprecedented and definitive blessings under His Divine Providence.

At no other time, and in no other place in human history did a people, through thoughts, words and deeds, create a culture that generated such improvement in the quality of life for all mankind.

History declares the first settlers of the colonies that would become the United States were Christians seeking religious freedom. For those distant from the facts we offer this brief review. The first Colony, Virginia, and the Charter of 1606 assigned land rights for the purpose of the “propagation of the Christian religion.” Massachusetts was the second founded in 1620, by Puritans, calling themselves Pilgrims after those sojourners in the Bible, seeking religious and cultural freedom, what we have seen articulated by John Winthrop as a “city on a hill.” New Hampshire came third, established by John Wheelwright, a Puritan priest from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Maryland was forth in 1634 founded by the Catholic Lord Baltimore, as refuge and a settlement for adherents to the Roman traditions fleeing oppression of the Anglican church. Connecticut was founded in 1636 by Thomas Hooker a leading Reverend of the Massachusetts colony as an additional settlement for Puritans. It was a sermon by Reverend Hooker on the Principles of Government that inspired the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut which scholars regard as an important evolution in the democratic government to eventually emerge in America. Puritan minister Roger Williams founded Rhode Island in 1836 and according to author John Barry, Williams was “a staunch advocate for religious freedom, separation of church and state, fair dealings with the Native Americans and an original abolitionist.”

Delaware was first established by the Dutch as New Netherlands, under the predominant religion of the Christian Dutch Reformed Church. Historians recognize the colony as the genesis of official religious pluralism in America. Founding documents stipulate that “everyone shall remain free in religion and that no one may be persecuted or investigated because of religion.” Christians from a successful Virginia colony needing more land founded what became the Carolinas in 1653, later delivered by King Charles to Nobles that engineered his Restoration to the throne. They enticed settlers with promises of religious toleration and freedom from the oppression in England. New Jersey was founded in 1664 offering Concessions and Agreements, rights unavailable in England: freedom of religion, freedom from persecution for religious beliefs, land, and the right to manage their own affairs. New York, came officially into English possession in 1674 through the Treaty of Westminster with the Dutch, and was named for the Duke of York, brother of King James. The former Dutch colony boasted the same Christian origins and religious pluralism as Delaware. Pennsylvania was founded in 1682 by namesake William Penn as a refuge for Quakers seeking freedom from the religious persecutions in England. The last of the original colonies, Georgia, was established in 1732 by James Oglethorpe, a Christian, as a home for the economically disadvantaged in England.

Though perhaps invisible to naysayers, God features prominently is our unique and definitive Declaration of Independence: we find reference to ‘the Laws of Nature and Nature’s God’; to men endowed by ‘their Creator’; an appeal to ‘the Supreme Judge of the world’; and finally, ‘with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.’ Of course, sacred means ‘of a religious rather than a secular purpose and so deserving veneration; connected with God.’ Indeed, of the 56 founders, beyond belief in God , fully 24 held degrees from seminary or bible colleges.

Further, our Founding Fathers to a man were believers convinced that God, creator of the universe, played a hand in human affairs on earth through his Divine Providence. Benjamin Franklin said, “Here is my creed. I believe in one God, the Creator of the Universe. That he governs it by His Providence. That he ought to be worshipped.” Father of our Country George Washington, not only believed in God, “the Almighty being who commands the universe,” but this firsthand witness and main actor at the exact center of all of the great events, plans and battles, the man historians acclaim as the indispensable man, later said he believed “the hand of Providence” had delivered American Independence, that “there was no other way to explain it.”

In the time of the Colonies and early Republic, in addition to public sermonizing by clergymen of all denominations, it was common for civic leaders throughout all the colonies and at all levels of government to call for days of fasting, humiliation and prayer. A reviewer of the book “American Prayers” suggests it proved that Christianity “completely saturated the daily life in early America.”

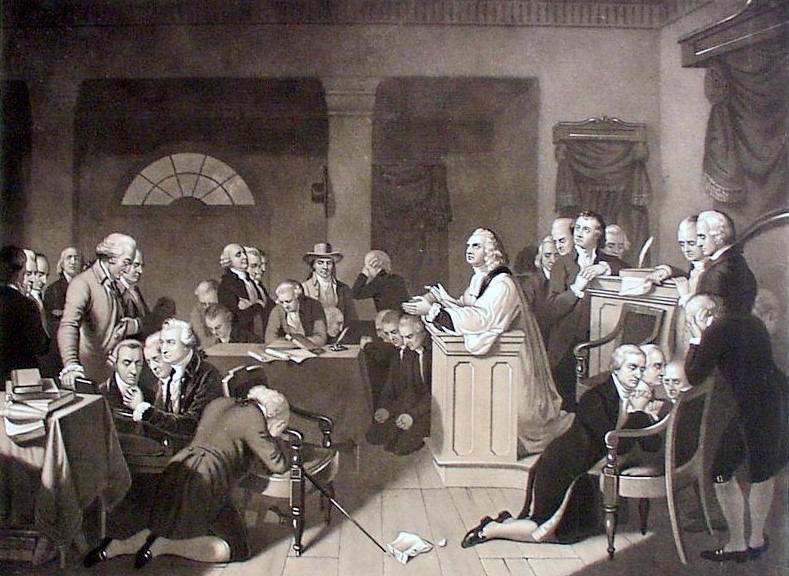

Prayers to God were conducted at every session of the First Continental Congress convened in 1774. Following the first prayer by the assembled, John Adams reports: “I never saw a greater effect produced upon an audience … George Washington was kneeling there, alongside him Patrick Henry, James Madison and John Hancock. By their side there stood, bowed in reverence, the Puritan patriots of New England … They prayed fervently for America, for Congress … And who can realize the emotions with which they turned imploringly to heaven for divine help. It was enough to melt a heart of stone. I saw the tears gush into the eyes of the old, grave, pacifist Quakers of Philadelphia.”

The habit of prayer continued with the Second Continental Congress, gathered in May 1776, who implored that the Nation: “through the merits and mediation of Jesus Christ, obtain his pardon and forgiveness; humbly imploring his assistance … And it is recommended to Christians, of all denominations, to assemble for public worship, and to abstain from servile labour and recreations on said day.” Regardless of alternate viewpoints, it is inescapable that colonial Americans believed in God and prayed for the beneficial guiding hand of Divine Providence in their personal and national affairs.

Further evidence that America was a nation under God is found in the origin of literacy and education in the Colonies. Christians catalyzed an explosion in literacy with the advent of the printing press in the 15th century and the publication of the Gutenberg Bible. Overnight, Christians throughout Europe and beyond hungered for the ability to read the Bible and express their thoughts in writing to others. Education was a foundation of faith and nowhere more developed than in Scotland, where from 1560 it was a mission of the Presbyterian Church to have a school in every parish. By the time of the American Revolution, Scotland was the most literate country in the world. For Christians, faith was firmly interwoven with education. It was certainly the case in America, where education quickly developed, based upon Scottish Enlightenment models. It is a remarkable fact of history that each of President George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe and Chief Justice James Marshall were schooled by Scottish Enlightenment Presbyterian tutors to the age of 16. Madison said, “Cursed be all that learning that is contrary to the Cross of Christ.”

Virtually every American university founded in the colonial period was established by Christians for the benefit of the propagation of the faith and training clergy for teaching the Gospel. Of the nine ‘colonial colleges’ formed before Independence, each owed its establishment to affiliation with Christian religious orders. Our best known and oldest, Harvard, was founded in 1636 by citizens of Massachusetts to avoid ‘leaving an illiterate ministry to the churches’ and named for minister and benefactor John Harvard. College of William and Mary was second, dedicated by Episcopalians. Yale was founded by clergy in 1701 to train Congregational ministers; and so on.

The idea of Rational Religion was seized upon by Gaelic Christian scholars like John Scotus Eriugena, acclaimed as having synthesized the philosophical thinking of twenty centuries, ancient pagan Greece with medieval Christian theology, and Duns Scotus who articulated the first formal discussion of the social contract among free people and rule by consent of the governed. For Eriugena, like St. Augustine before him, true philosophy did not differ from true religion. “What is philosophy but an expounding of the rules of religion whereby man humbly adores and rationally seeks God, the highest cause and source of everything.”

Rational Religion found God in Man and Nature and ignited the Protestant Reformation which released people from the tyranny of Bishops of the Church as the Scottish Enlightenment released them from the tyranny of the King of State. Notions of freedom under God were strongly held and widely proclaimed and following the teaching delivered from Scotland to the American pulpit, colonists came to believe that no law was above God’s law, the genesis of the motto of the American Revolution: “No king, but King Jesus!

Thomas Reid was a major influence in the Scottish Enlightenment and articulated what became the standard moral philosophy of colonial America. Reid was born in Aberdeen and educated at parish schools and then the University of Aberdeen. He was ordained a minister of the Church of Scotland. While a professor at the University of Aberdeen he wrote, An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense, and following was appointed Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow, succeeding Adam Smith.

In the Age of Enlightenment, primarily on the Continent, there were those seeking justifications for release from what they considered the moral constraints suggested by Christian belief. Philosophical skepticism developed as a branch of thought, and in many ways the Scottish School of Common Sense Realism developed in response. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy details that “Common Sense Philosophy arose to refute philosophical skepticism which sought to discredit doctrines of belief in God.”

The Common Sense School taught that every person had ordinary experiences that provided intuitively certain assurance of a) the existence of the self, b) the existence of real objects that could be seen and felt; and c) certain “first principles” upon which sound morality and religious beliefs could be established. Adherents to Common Sense believed that God exists, has a plan for his people and acts for their benefit through divine intervention, revealed through Jesus Christ, to save humanity. This thinking was unquestionably the mindset of colonial theologians and the mindset of Americans in general.

Common Sense, according to Benjamin Redekop “dominated thought in Scotland” and was “the orthodox philosophy of colleges and Universities, providing the intellectual bedrock for the Enlightenment.” John Witherspoon was a Scottish minister educated at the University of Edinburgh that was recruited to the College of New Jersey by Presbyterians to revitalize the institution. Under Witherspoon Princeton became the locus of Scottish Enlightenment Common Sense philosophy in America. It is ironic that today a Princeton professor of history could write a book disclaiming a Christian America, when Princeton, from the Presbyterian Log College, to the College of New Jersey, to Rush, Stockton, Witherspoon, Madison and eventually the Theological Seminary, was not only solidly Christian in belief, but perhaps the most influential intellectual engine for Independence in the Colonies that became America.

Common Sense was the intellectual bedrock for the American Revolution. Common Sense held as a first principle belief in God, was the predominant philosophy of the Colonies, among the clergy, the educational professionals and the people. It is no coincidence that philosopher activist Thomas Paine named his pamphlet Common Sense, or that today it is attributed by historians as the spark that ignited the drive for Independence, or that it remains, outside the Bible, the most widely read publication in American history.

When Rational Religion combined with Common Sense philosophy the result was Republican Theology. The only rational way to govern people that are free and equal is by their consent, in a Republic, under God. And for ministers who provided the foundation for American Independence, republican freedom would only be ensured by virtue.

Benjamin Rush was a Founding Father of remarkable virtuosity. He was born near Philadelphia, and similar to those named above, was tutored by a Scottish Enlightenment Presbyterian scholar in his youth. He received his bachelor’s degree from Princeton at 14 and became a medical Doctor graduated from the University of Edinburgh. Dr. Rush was a signer of the Declaration, member of the Continental Congress, Surgeon General of the Army for Washington and founder of Dickenson University. He was an abolitionist, established schools and bible associations for blacks, was the Country’s first professor of both Chemistry and Psychiatry and advised on the medical supplies carried by the Lewis & Clark Corps. of Discovery.

In The Republican Theology of Benjamin Rush, Professor D’Elia quotes Benjamin Rush, “A Christian cannot fail of being a republican. The history of the creation of man, and of the relation of our species to each other by birth which is recorded in the Bible is the best refutation that can be given for the divine right of kings, and the strongest argument that can be used in favor of the original and natural equality of all mankind. A Christian, I say again, cannot fail of being a republican, for every precept of the Gospel inculcates those degrees of humility, self-denial, and brotherly kindness, which are directly opposed to the pride of monarchy and pageantry of a court.”

Our Founding Fathers believed in God. (And though a topic for another day, they believed in the abolition of the institution of slavery that was a part of their world.) They believed in living God-honoring lives. They believed that the freedom and equality promised by God was only possible within a Republican form of government. And, they believed that a republican government was reliant on religion. A republican government could not survive without public virtue, public virtue could not manifest absent private virtue, and private virtue dependent upon religion. Our Founding Fathers believed that self-government, a democratic republic, could only succeed among those, self-governed.

By 1777 a minister by the name of Abraham Keteltas linked “the cause of liberty against arbitrary power” with “the cause of pure and undefiled religion,” proclaiming that the revolutionary era expected the time when “the kingdoms of this world are become the kingdoms of our Lord and his Christ.” The Puritan ideal of the Pilgrims effectuated, now, the republic as “God’s American Israel.”

John Hancock, first signer of the Declaration, said, “Resistance to tyranny becomes the Christian and social duty of each individual. … Continue steadfast and, with a proper sense of your dependence on God, nobly defend those rights which heaven gave, and no man ought to take from us.”

George Washington said, “While we are zealously performing the duties of good citizens and soldiers, we certainly ought not to be inattentive to the higher duties of religion. To the distinguished character of Patriot, it should be our highest glory to add the more distinguished character of Christian.”

To quote Benjamin Rush, “The foundation for useful education in a republic is to be laid in religion. Without this there can be no virtue, and without virtue there can be no liberty, and liberty, is the object of all republican governments.”

John Adams said, “Public virtue cannot exist in a Nation without private virtue, and public virtue is the only foundation of Republics. We have no government armed with power capable of contending with human passions unbridled by morality and religion. Our constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

And James Madison, 4th President, ‘Father of the Constitution’ and author of ‘The Bill of Rights’ said,

“We have staked the whole future of our new nation, not upon the power of government, far from it. We have staked the future of all our political constitutions upon the capacity of each of ourselves to govern ourselves according to the moral principles of the Ten Commandments.”

With the recognition that regardless of revisionist history and selective national memory, America was once One Nation Under God, four corollary principles quickly become apparent:

1. Prosperity is uniquely and definitively downstream from Christianity – As Cotton Mather proclaimed, “Religion begat Prosperity’ – the aggregate God honoring applied Christian living of our forefathers combined with His Providential blessings to create EVERYTHING America has and has done for her people and the world – from America’s founding the greatest flourishing of liberty, literacy, learning, education, industry, progress, prosperity, service and charity in the human history;

2. For whatever reason, there are people that object to a unified America enjoying the demonstrated cultural and economic blessings of living under God, and are determined to overthrow it;

3. We must do everything we can, for ourselves, our children and the world, to understand and maintain America as One Nation Under God; and,

4. We must determinedly love and provide examples and opportunity for all to become a part of that One Nation Under God.

For “the Fruit of the Spirit Spirit is love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. Against such things there is no law.” Galatians 5:22-23

Pastor Dockerty stipulated that the ‘under God’ of his suggested formulation for the Pledge of Allegience was broad enough to include Jews and Muslims. And Founding Father Patrick Henry, while famous for ‘Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death’ also said, ”It cannot be emphasized too strongly or too often that this great nation was founded, not by religionists, but by Christians; not on religions, but on the gospel of Jesus Christ. For this very reason peoples of other faiths have been afforded asylum, prosperity, and freedom of worship here.”

One Nation Under God, indeed.

Scotus

Kevin Kruse, One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America, 2016

New York Times 1619 Project

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html

Christopher McCormick, Countries with Better English Have Better Economies, Harvard Business Review, 2013

https://hbr.org/2013/11/countries-with-better-english-have-better-economies

Liberty Language Services

https://www.libertylanguageservices.com/post/what-percentage-of-people-in-the-us-speak-english

Daniel Rogers, As a City on a Hill: The Story of America’s Most Famous Lay Sermon, Princeton University Press, 2018

Paul Squires, The Politics of Sacred in America: The Role of Civil Religion in Political Practice, Springer, New York, 2018

Christopher Richmann, America as New Jerusalem” Word & World, 2020

http://wordandworld.luthersem.edu/contents/pdfs/40-2_Jerusalem/40-2_Richmann.pdf

Nathan Hatch, The Sacred Cause of Liberty: Republican Thought and the Millennium in Revolutionary New England, Yale University Press, 1977

Paul Russell and Anders Kraal, Hume on Religion, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2017

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hume-religion/

Daniel D’Elia, The Republican Theology of Benjamin Rush, Pennsylvania History Journal, 1966

photo credit: T. H. Mattison, The First Prayer in Congress, 1848